New research gives us insights into history’s first well-documented businesswomen, who made their mark earlier than you may think.

Around 1870 BC, in the city of Assur in northern Iraq, a woman called Ahaha uncovered a case of financial fraud.

Ahaha had invested in long-distance trade between Assur and the city of Kanesh in Turkey. She and other investors had pooled silver to finance a donkey caravan delivering tin and textiles to Kanesh, where the goods would be exchanged for more silver, generating a tidy profit. But Ahaha’s share of the profits seemed to have gone missing – possibly embezzled by one of her own brothers, Buzazu. So, she grabbed a reed stylus and clay tablet and scribbled a letter to another brother, Assur-mutappil, pleading for help:

“I have nothing else apart from these funds,” she wrote in cuneiform script. “Take care to act so that I will not be ruined!” She instructed Assur-mutappil to recover her silver and update her quickly. “Let a detailed letter from you come to me by the very next caravan, saying if they do pay the silver,” she wrote in another tablet. “Now is the time to do me a favour and to save me from financial stress!”

Ahaha’s letters are among 23,000 clay tablets excavated over the past decades from the ruins of merchants’ homes in Kanesh. They belonged to Assyrian expats who had settled in Kanesh and kept up a lively correspondence with their families back in Assur, which lay six weeks away by donkey caravan. A new book gives unprecedented insight into a remarkable group within this community: women who seized new opportunities offered by social and economic change, and took on roles more typically filled by men at the time. They became the first-known businesswomen, female bankers and female investors in the history of humanity.

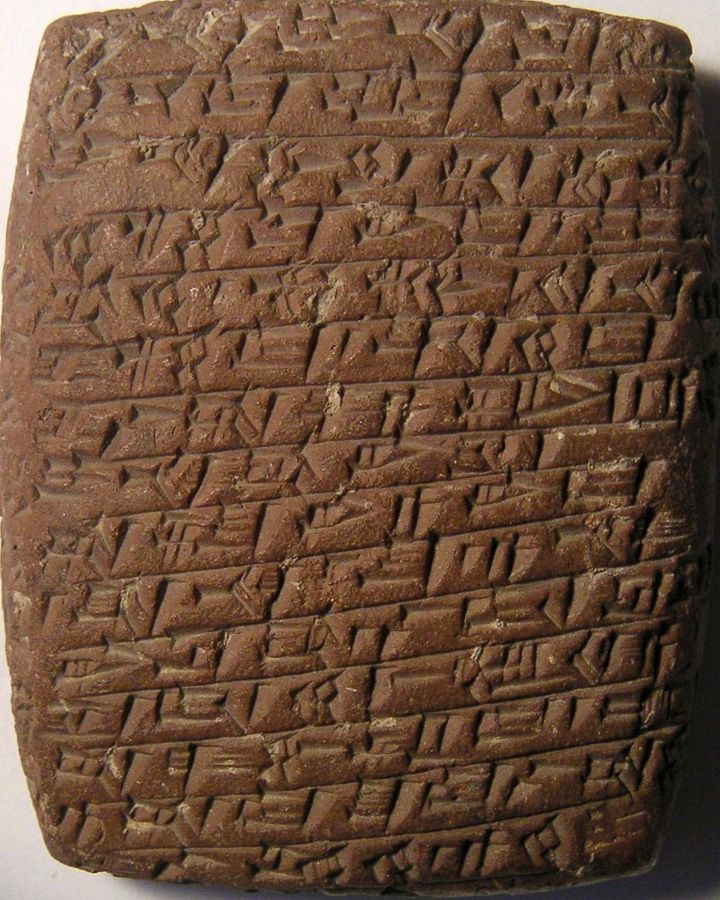

‘Strong and independent’ The bulk of the letters, contracts and court rulings found in Kanesh date from around 1900-1850 BC, a period when the Assyrians’ trading network was flourishing, bringing prosperity to the region and giving rise to many innovations. The Assyrians invented certain forms of investment and were also among the first men and women to write their own letters, rather than dictating them to professional scribes. It’s thanks to these letters that we can hear a chorus of vibrant female voices telling us that even in the distant past, commerce and innovation were not the exclusive domains of men. The letters, though tiny, contained a wealth of insight into this ancient world of commerce (Credit: Cecile Michel, Archaeological Mission of Kültepe)

The letters, though tiny, contained a wealth of insight into this ancient world of commerce (Credit: Cecile Michel, Archaeological Mission of Kültepe)

While their husbands were on the road, or striking deals in some faraway trading settlement, these women looked after their businesses back home. But they also accumulated and managed their own wealth, and gradually gained more power in their personal lives.

“These women were really strong and independent, because they were alone, they were the head of the household while the husband was away,” says Cécile Michel, a senior researcher at the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) in France, and author of the book, titled Women of Assur and Kanesh. Through more than 300 letters and other documents, the book tells a strikingly detailed and colourful story of the women’s struggles and triumphs. Though brimming with drama and adventure, the clay letters themselves are tiny, about the size of the palm of a hand.

The businesswomen’s story is tied to that of the Assyrian merchant community as a whole. In their heyday, the Assyrians were among the most successful and well-connected traders of the Near East. Their caravans of up to 300 donkeys criss-crossed mountains and uninhabited plains, carrying raw materials, luxury goods and, of course, clay letters.

“It was one leg of a huge international network, which started somewhere in Central Asia, with lapis-lazuli from Afghanistan, carnelian from Pakistan, and the tin may have come from Iran or further to the east,” says Jan Gerrit Dercksen, an Assyriologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, who has also worked on the Kanesh tablets. Foreign traders brought these goods to the gates of Assur, along with textiles from Babylonia in southern Iraq. They were sold to the Assyrians, who packed them onto caravans bound for Kanesh and other towns in the Anatolian region in Turkey, where they were sold for gold and silver. Complex financial instruments facilitated this trade, such as the “naruqqum”, which literally means “bag”. It refers to a joint-stock company in which Assyrian investors pooled their silver to fund merchant-led caravans over many years. The merchants also developed a lively business jargon. “The tablet is dead” meant that a debt had been paid and the clay-tablet contract recording it was therefore cancelled. “Hungry silver” referred to silver that was not being invested, idly sitting around instead of generating a profit.

They really are accountants; they know perfectly well what they should get back in exchange for their textiles – Cécile Michel

Assyrian women contributed to this bustling commercial network by producing textiles for export, issuing loans to merchants, buying and selling houses, and investing in naruqqum schemes. Their skills as weavers allowed them to earn their own silver. They kept a keen eye on foreign fashions and market trends to secure the best prices, as well as on taxes and other costs that dented their profits.

“They really are accountants. They know perfectly well what they should get back in exchange for their textiles. And when they earn this money from the sale of their textiles, they pay for the food, for the house, for daily life, but they also invest,” says Michel, who has also co-created a new documentary about the women.

‘Guardians of the archives’ This commercial acumen allowed some to slip into positions that were unusual for women at the time, by functioning as their husbands’ trusted business partners. The traders in turn benefited from having literate and numerate wives who could help with day-to-day business as well as emergencies. One Assyrian merchant writes to his wife, Ishtar-bashti: “Urgent! Clear your outstanding merchandise. Collect the gold of the son of Limishar and send it to me… Please, put all my tablets in safekeeping.” Others ask their wives to pick specific tablets from the household’s private archives to find financial information or settle a business matter. The ancient city of Kanesh, also known as Kültepe mound, in what is now Turkey (Credit: Archaeological Mission of Kültepe Archives)

The ancient city of Kanesh, also known as Kültepe mound, in what is now Turkey (Credit: Archaeological Mission of Kültepe Archives)

“Since they were the ones to stay at home, they were the guardians of the archives,” Michel says of the women. “You have to remember, these contracts represent a lot of money, for example the loan contracts and so on.”

The women in turn don’t shy away from sending their husbands or brothers instructions and admonishments. “What is this that you do not even send me a tablet two fingers wide with good news from you?” an Assyrian woman called Naramtum writes to two men. She complains about a dispute involving debt and lost merchandise, and urges the men to resolve it, closing with a brisk: “Send me the price of the textiles. Cheer me up!” Another chided her brother over a missing payment: “Don’t be so greedy that you ruin me!”

These women’s independence stood in stark contrast to some other societies in the ancient Near East, such as nearby Babylonia in southern Iraq. Michel points out that in Assur, as in Kanesh, both the wife and the husband could ask for a divorce and would be treated the same in the proceedings. “But at exactly the same time in Babylonia, in the south of Babylonia, the wife couldn’t ask for a divorce, and in the north of Babylonia, if she dared to ask, she would be put to death.”

With that strengthened economic influence came better conditions in the women’s personal lives. A number of them added clauses to marriage contracts that banned the men from taking second wives or travelling by themselves, as in this example: “Assur-malik married Suhkana, daughter of Iram-Assur. Wherever Assur-malik goes, he shall take her with him. He shall not marry another woman in Kanesh.”

At some point, for reasons that are somewhat unclear, trade between Assur and Kanesh declined. Eventually, Kanesh was deserted. Other cities and communities took over as engines of commerce, creativity and cultural exchange. But the women’s clay tablets, hardened by house fires, remained in the abandoned homes to be discovered thousands of years later. They capture a female experience so rarely documented in history, not of queens or high priestesses, but of working women wondering how to get through the next day. As Michel says, in other Mesopotamian cities, letters written by women have also been found, “but there are not so many. [Kanesh] is unique for that.” And with roughly half of the tablets of Kanesh still unread, there are surely many more secrets waiting to spill out.